Vanity Fair – Letters From Hollywood Gives New Life to Vintage Scandal and Gossip

Letters From Hollywood Gives New Life to Vintage Scandal and Gossip

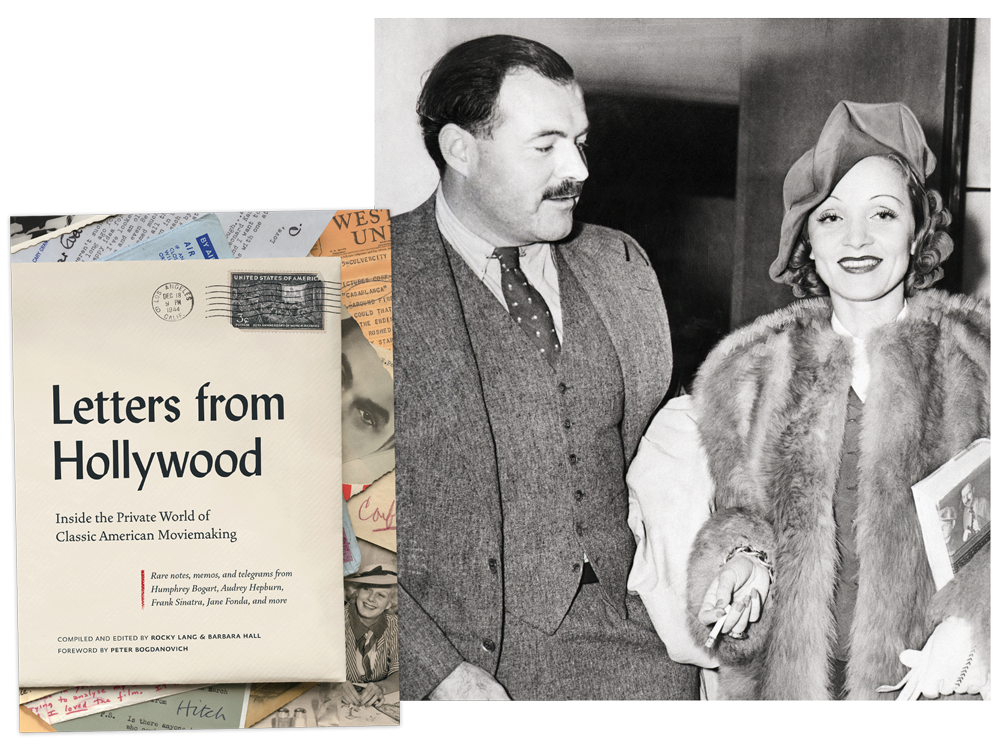

Collaborators Rocky Lang and Barbara Hall—and contributor Eva Marie Saint—preview their new book, featuring missives about everything from James Bond (“New York did not care for [Sean] Connery”) to Marlene Dietrich and Ernest Hemingway’s unconsummated love.

BY DONALD LIEBENSON

SEPTEMBER 10, 2019

Ernest Hemingway and Marlene Dietrich in 1938. ABOVE, FROM BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES.

Before Gyl Roland, daughter of actor Gilbert Roland, gave Rocky Lang permission to print a passionate letter her father wrote to silent-screen siren Clara Bow, she wanted something in return. Lang—who went to great lengths to secure the rights to dozens of vintage missives for his coffee-table book, Letters from Hollywood—is himself a Hollywood scion: His father was Jennings Lang, an agent celebrated for his A-list clients, but infamous for a scandalous affair that found him on the wrong end of a jealous husband’s gun.

In short: In 1951, Jennings was having an affair with actor Joan Bennett—the wife of producer Walter Wanger, and Gyl Roland’s aunt. When Wanger learned this, he retaliated in spectacular fashion—by allegedly shooting Jennings in the balls.

“We chitchat about the book,” Lang recalled in an interview. “And Gyl says, ‘You know who I am, don’t you?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do.’ She says, ‘You do know I know who you are.’ I said, ‘I know.’ Huge dramatic pause—and she says, ‘Well, was Walter accurate [in his aim]?’ And I said, ‘No, or I wouldn’t be here talking to you.”

According to Lang, Jennings was actually shot in the upper thigh. Satisfied with his answer, Roland gave him the okay to print the letter.

Letters from Hollywood, compiled by Lang and film historian and researcher Barbara Hall, is a priceless treasure trove of more than 130 letters, telegrams, memos, and other missives dating from 1921 (Harry Houdini to producer Adolph Zukor) to 1976 (Jane Fonda to her Julia director, Fred Zinnemann). Each is presented chronologically, and reproduced in its original form; the elegantly designed hotel stationery letterheads alone are almost worth the price of admission.

It is a personal epistolary history of Hollywood, as told by the people who lived and worked there. As Peter Bogdanovich writes in the book’s foreword, “This is a delightfully intimate and illuminating way to learn about Hollywood history.”

Several letters call to mind Oscar-winning screenwriter William Goldman’s classic Hollywood maxim, “Nobody knows anything.” Consider the 1961 telex to producer Harry Saltzman from his partner “Cubby” Broccoli, who was seeking a leading man to portray James Bond in Dr. No. “New York did not care for [Sean] Connery,” Broccoli reports. “Feels we can do better.”

Or try a 1945 letter from playwright and screenwriter Robert Sherwood, which Lang calls one of his favorites in the book. In it, Sherwood tries to convince producer Samuel Goldwyn to abandon the proposed postwar drama that would become The Best Years of Our Lives, arguing that it “will be doomed to miss the bus.” Years would go on to win seven Oscars in the main competition categories—including best picture and, for Sherwood, best screenplay—plus an honorary award.

“It resonated with me,” Lang said. “One, as a movie I love; two, it’s a great piece of film history; and three, as a filmmaker, I’m constantly dealing with creative and executive people trying to guess the market.”

For Lang, who has been in the film business for 35 years as a producer, writer, and director (White Squall, Girl Fight), one letter in particular—shared with him by Howard Prouty, then the acquisitions archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—hit home, inspiring him to compile Letters from Hollywood.

Dated April 14, 1939, it was written by his father to celebrated literary agent H.N. Swanson, asking for a job. “Ten minutes with a young personable attorney, with years of drama and screen criticism experience, and with a living desire to imitate you and your position might not prove boring,” the young go-getter wrote. “Please see me?”

“My dad was 24 years old,” Lang said. “He had just come off the train from New York with $100 in his pocket…. He went on to represent Joan Crawford and Humphrey Bogart, and later produced the sequels to Airport, as well as Earthquake. He gave Clint Eastwood and Steven Spielberg their first [theatrical] directing gigs. His whole life was ahead of him, and the letter moved me so much.”

Prouty recommended that Lang collaborate with Hall, who was a special-collections researcher at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library before becoming an archivist for the Art Directors Guild. She was familiar with the archives that preserve the collections of film-business professionals. What sorts of letters were she and Lang looking for? “Rocky and I talked about this a lot,” she told Vanity Fair. “We were looking for letters that revealed something about what it was like to live and work in Hollywood. We wanted to get some big names, but we also wanted to include letters by someone who wasn’t as well-known or remembered, if [the letter writer] had an amazing voice or revealed something about Hollywood that maybe we hadn’t seen before. I particularly like, for instance, the 1933 letter from cameraman Bert Glennon to Katharine Hepburn. You could tell they were great friends.”

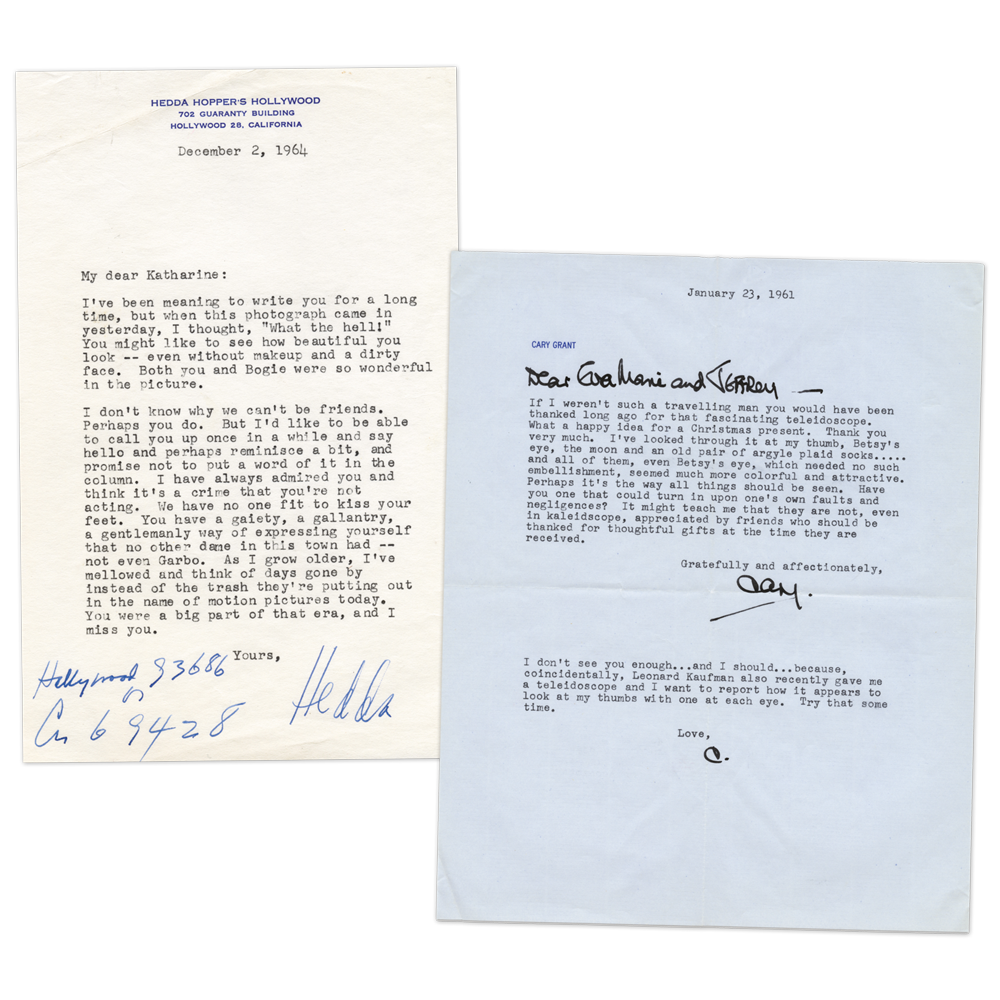

ABOVE, COURTESY JOAN HOPPER PEAT-JAMES; RIGHT, COURTESY OF THE CARY GRANT FAMILY.

Better-known friends were Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, who costarred in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Letters from Hollywood includes a charming 1961 letter from Grant to Saint and her husband, director Jeffrey Hayden, belatedly thanking them for a teleidoscope the couple sent him for Christmas. In a phone interview with Vanity Fair, Saint, 95, did not recall the letter, but it sparked vivid memories of meeting Grant on the set. “He said to me, ‘Now, Eva Marie, you don’t have to cry in this movie; we’re going to have a great time.’ Isn’t that the dearest?”

Letter writing, Saint said, is something of a lost art. “I have my computer…but I still get letters,” she said. “Very often it will be someone who says they have my email, but that they just wanted to write to me. That’s so sweet. I have envelopes and my stationery ready to write them back and thank them.”

Much more than friends were Marlene Dietrich and Ernest Hemingway, whose unconsummated love burns red hot in a 1955 billet-doux written by Dietrich. It begins with “Well, you, my eternal love,” and ends, “Please write to me about everything, how you are and Mary [Hemingway’s fourth wife] and what you are thinking and if you still love me.” She signs it, “Your Kraut.”

Many of the entries in Letters from Hollywood offer an invaluable inside look at the business of show: Bette Davis threatening to walk out unless studio head Jack Warner gives her a more artist-friendly contract; director Joseph Mankiewicz lamenting to producer Darryl F. Zanuck that he cannot complete All About Eve within the studio’s allotted tight schedule; Zanuck negotiating with Production Code Administration chief Joseph Breen about the John Ford Western My Darling Clementine’s depiction of “whiskey drinkers, gun toters, and prostitutes.”

In the ever ongoing battle between filmmakers and the executives, Lang and Hall each noted, some things never change.

Hall hopes that this book conveys the importance of film archives as a resource to “learn about Hollywood history in the words of the people who were there.”

She also hopes it expresses an appreciation for the art of letter writing. “No matter how convenient it is to have all these other forms of communication,” she said, “there is something about letter writing they can’t replicate…. It’s like the person’s personal imprint goes into the letter.”

The book’s most charming example of this is a 1974 letter written by 17-year-old Thomas Hanks to George Roy Hill, the freshly minted Academy Award–winning director of The Sting. In the most Hanksian way possible, the future two-time best actor angles to be discovered. “My looks are not stunning,” he writes. “I am not built like a Greek God, and I can’t even grow a mustache, but I figure if people will pay to see certain films (The Exorcist, for one) they will pay to see me.”

“There is nothing more personal than handwriting,” Saint said.

That’s why the Eva Marie Saint papers, housed in the special-collections department at the Margaret Herrick Library, actually don’t contain her cherished cache of letters written to her by her beloved husband of 65 years, who died three years ago. “Jeff and I wrote so many letters to each other; he was on location, and I was on location,” she said. “They are close to my heart. I have a stack that no one will ever see.”